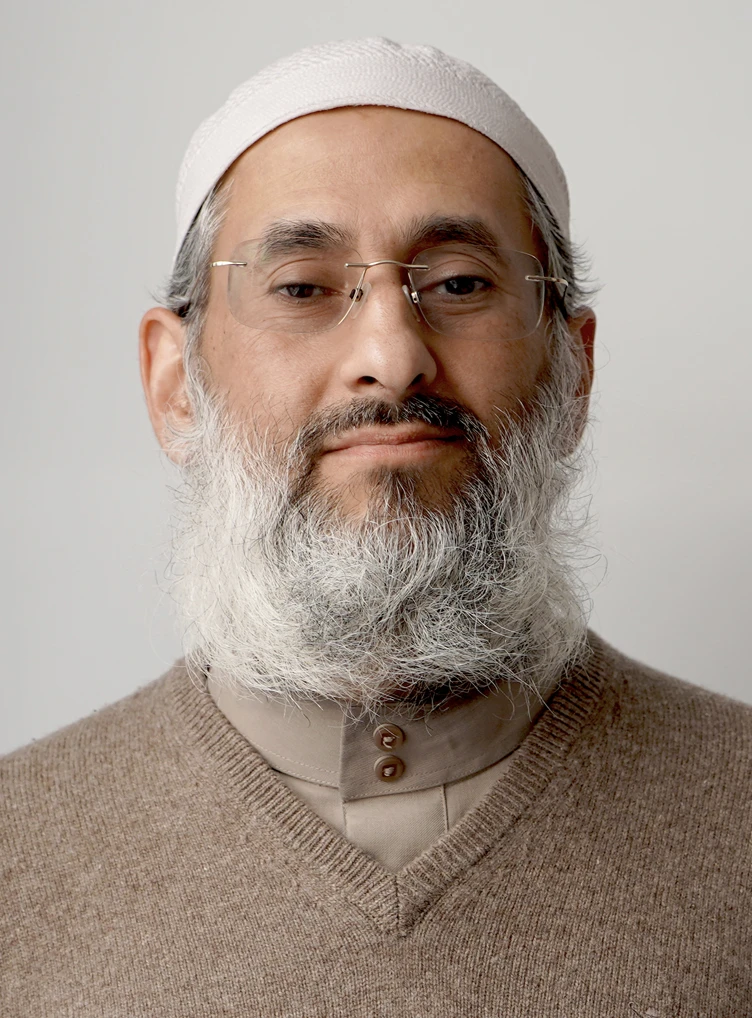

Vulnerable people are suffering as banks become increasingly reluctant to deal with humanitarian organisations working in conflict zones and fragile states, points out Islamic Relief’s Khaleel Desai.

In the middle of a recent dry season in Somalia, villagers desperately need water for their families and livestock. Islamic Relief had planned to repair 15 boreholes in the area, to provide a sustainable supply of clean water. Despite meeting all our compliance and assurance requirements, funds for the boreholes were held up in the international banking system for more than 6 months before eventually being made available.

The delay left thousands of people without a reliable water supply and put lives at risk.

This is despite Islamic Relief Worldwide’s global reputation for working in the hardest-to-reach areas. We are trusted by international governments, donors and the United Nations to provide aid in places such as Yemen, Syria and Somalia, and this work is routinely independently audited.

It brings into sharp focus the dire consequences of what is too easily categorised as simply administrative hoops to jump through. Delays are increasingly common across the humanitarian sector. And often delay, rather than all-out denial of service, is the best many humanitarian organisations can hope for.

What is financial de-risking?

It is of course legitimate and necessary for states to ensure the security of their population, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) like us work closely with banks to prevent money from getting into the hands of terrorists, abiding by the Counter-Terrorism Financing (CTF) measures put in place after the September 11 terrorist attacks.

However, some governments and financial institutions have misinterpreted these measures, and overestimated the actual risk of such funds being diverted. This has led to so-called ‘de-risking’, in which banks are reluctant to deal with humanitarian charities working in some of the world’s most fragile states.

Rather than assess each transfer on a case-by-case basis, some ‘de-risk’ and do not allow any money into risky locations, or do not engage with organisations they believe to be higher risk.

This is clearly the opposite of the ‘risk-based approach’ the sector has been advocating. Also, many donors are not sharing risk in the delivery of their programmes, but simply leaving localised, humanitarian organisations to navigate legal, compliance and due diligence requirements that are forcing them out of the picture.

Why is this a worrying trend?

This has devastating unintended consequences. It causes significant delays and at times even completely blocks legitimate humanitarian aid for some of the most vulnerable people, and by those people who are within and from those communities.

International charities like Islamic Relief need to move money from one place to another and across borders – to fund projects like the boreholes in Somalia, or to pay salaries of staff in field offices, buy equipment or hire vehicles. We also need to empower and work with local humanitarian actors who are best placed to respond – for example, see our work in Yemen.

If these transactions can’t take place, humanitarian projects are delayed.

Some sections of civil society are disproportionately affected, particularly Muslim faith-based, diaspora and smaller local organisations. These play a crucial role in humanitarian responses, but they are increasingly forced to stop operations as they are not able to secure financial services or meet due diligence obligations which are designed for larger, better-equipped NGOs in the Global North.

De-risking not only delays projects but has also led to donors prioritising locations and activities to which they can more easily transfer funds – rather than where needs are highest. In Syria, for example, a study by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and London School of Economics (LSE) found that humanitarian organisations have adjusted their programmes to focus on less contentious areas and projects that are less vulnerable to bank obstruction. Again, this means the people who are most in need of aid are the ones that are prevented from receiving it.

This is not a new phenomenon, but it has become more obvious in recent years and the impact is increasing.

This needs to change

Islamic Relief is at the forefront of bringing attention to these issues and the impact they are having.

We are working with the United Nations, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and as part of UK and US government stakeholder dialogues, to advocate that measures to protect the NGO sector from terrorist abuse do not disrupt or discourage legitimate humanitarian activities.

Our new briefing note, Financial Inclusion for NGOs: Why should you care?, sets out recommendations for governments and financial institutions.

We must act now

We are calling on governments and banks to recognise the role played by NGOs in delivering aid in some of the world’s most remote and insecure areas, and to recognise that financial transactions for this work are not automatically high risk.

A ‘one size fits all’ approach to all NGOs is not appropriate or effective.

We all want to prevent aid getting into the hands of terrorists or armed groups. We also want to ensure aid gets to the women, men and children who are suffering from conflict, famine or poverty. To ensure both of these things we need governments and banks to work more closely with NGOs to find solutions, as we all want to achieve the same objective.

Only by working together can we effectively identify and manage the risks whilst ensuring smaller, localised or faith-based NGOs aren’t being forced out of the sector.